LETTER TO THE EDITOR

19 September 2019

Dear Editor,

The article ‘The History of Earned Value Management Through Incentives Plans’ in the September edition of PM World Journal, is fundamentally flawed. The paper’s title has no relationship to the conclusions, and the material, as presented, fails to support the presumption implied in the title.

Earned value management has three fundamental components:

- All of the resources and work planned and used in the course of a project is reduced to a single metric (usually money), this includes labor, materials, suppliers, subcontractors and overheads.

- The work is planned, and progress measured based on the ‘metric’ to derive the planned, earned and actual ‘values’, for the entire scope of work required to complete the project.

- As work progresses, the current difference between planned and actual performance (as measured by the metric) is used to forecast future outcomes.

The incentive schemes and piece rate payments described in the paper fail to achieve any of these fundamental objectives, and the issues discussed around ‘project failure’ while significant in themselves, have little relevance to either earned value or incentivization.

The fundamental problem ignored by the author is that incentive schemes focus on a very limited aspect of the work of a project (or manufacturing organization). The only aspect incentivized is that portion of the total scope of work undertaken by a team or an individual where predetermined performance targets can be set. There is always a lot of ‘other work’ for which incentive rates have not or cannot be set.

The concept of piece rate payments, which underpin most of the incentive schemes outlined in the paper, extend back into the ‘Dark Ages’. Stonemasons were paid by the number of ‘pieces’ of stone they cut and finished for use in the construction of castles, cathedrals, and other structures (which is why stones have ‘mason’s marks’ carved in the back). However, in this type of payment system the cost per item is pre-set and fixed, the employer always pays exactly the same amount, the variable is how much each individual earns in any given time period. Different workers working on the same task can earn very different amounts of money (but the cost to the ‘project’ per item and in total remains the same).

This fundamental limitation is compounded by the fact that apart from ‘profit sharing’, which has nothing to do with the management of a project, the various schemes listed all fail to deal with the cost and usage of materials, suppliers, subcontractors, supervisors, and other elements incorporated into earned value calculations. None of the systems attempt any form of aggregation, they are designed to focus on motivating individuals, or small teams.

The second failing is far more significant: none of the systems listed make any attempt to forecast future outcomes. Given there is no change in the set cost, there is no cost variability to measure, and while there is data that would allow some prediction of time outcomes, there is no evidence of anyone ever attempting this calculation for a ‘project’. The fact data could have been derived from these incentive systems that may have been capable of forecasting overall time outcomes based on actual performance is not particularly useful in the absence of any evidence this concept was used.

We know the ancient Babylonians were capable of calculating how long a gang of slaves would take to excavate a trapezoidal water canal based on the production rate for ‘slaves digging sand’. The process of estimating the cost of doing work is a constant for at least the last 4000 years, and nothing much changed through to the early 20th century. Similar calculations are used in incentive schemes, and are used in project cost estimating, but I would suggest all this shows is that project cost management and incentive schemes have common roots rather than one lead to the development of the other.

The closest I have been able to find of anyone deriving some form of overall measurement based on information in an incentive scheme is the work undertaken by Henry Gantt during WW1. He was able to assess the percent complete for the construction of a ship’s hull based on the number of rivets fastened by workers compared to the total number in a ship’s hull.

Gantt’s approach combined two sets of data, the total number of rivets needed to complete the hull derived from the drawings developed for the ship and the number of rivets fastened by the crews derived from the piecework payment records. Unfortunately, apart from recognizing the work was ahead or behind schedule and instigating actions to ‘catch up’ when needed, this concept seems to be a ‘dead end’. Extending on Gantt’s work to predict the time needed to complete each hull was feasible, but it did not happen (or, more accurately, is not recorded as occurring in his books), and, as with all of the other systems, the cost of the riveting was fixed and did not change – the workers still received a fixed price per rivet, and the total cost of riveting was known and fixed.

In summary, the objective of incentive plans is to motivate people to work harder, this is an important HR concept. But the concept of motivation has nothing to do with measuring the effect of this ‘incentivization’ on productivity, the overall cost of the work, and based on this predicting the consequences at project completion.

The shift in thinking from comparing planned to actual and then making arbitrary decisions based on that information to manage the work, to a paradigm where information is used to dynamically model future outcomes seems to have its roots in concept of ‘Operations Research’ (OR) which originated in the 1930s.

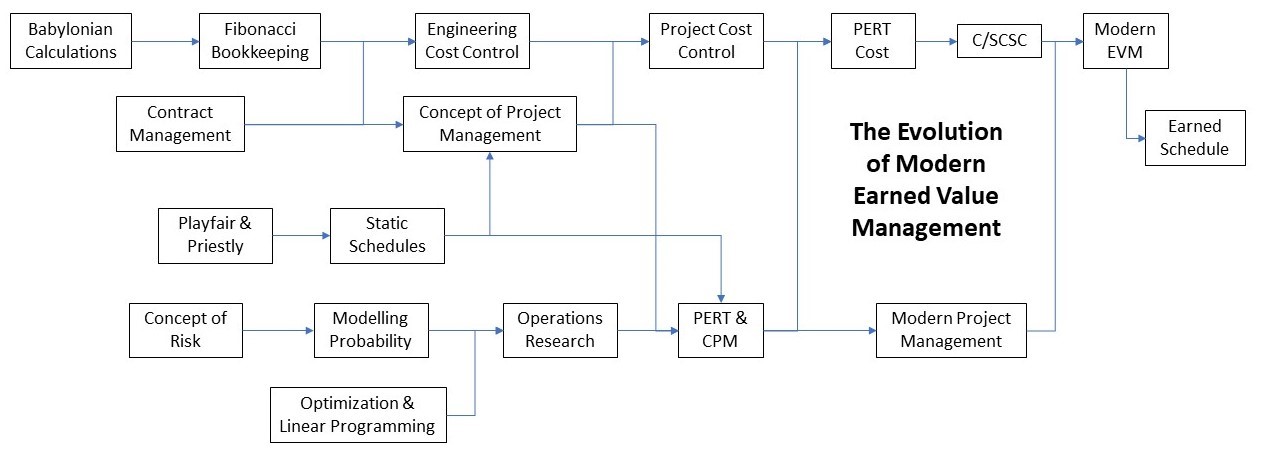

OR uses the mathematics of optimization and linear programming, applied to a scenario, to assess expected future outcomes. These concepts underpinned the systems used by the British Airforce in the ‘Battle of Britain’ and then went on to be applied on both sides of the Atlantic, in a wide range of situations where a range of outcomes was possible. OR was the foundation of critical path and PERT scheduling and the combination of PERT with project cost management (a concept that goes back to the 14th century at least) gave rise to PERT Cost, which in turn evolved in the C/SCSC and then into what we know today as ‘Earned Value’. The overall flow of developments looking something like this:

Note: this diagram is being developed for a paper on the origins of EVM which I hope to publish early in 2020. While many of the links are well documented, others still need more substantiation.

Note: this diagram is being developed for a paper on the origins of EVM which I hope to publish early in 2020. While many of the links are well documented, others still need more substantiation.

While it is true that both project controls (including earned value) and incentive systems rely on the ability to calculate the expected time and effort required to accomplish a task, all this shows is they have this common root. However, a common heritage which dates back to the Babylonians does not mean one influenced the other. The two systems are fundamentally different!

In summary, I would suggest the assertion contained in this paper that an incentive system that paid individuals a pre-set amount for work they have actually done (and pays different amounts to different people based on their individual efforts), somehow lead to a system that holistically looks at current performance and uses that information to predict future outcomes of a project, is, fundamentally flawed.

Yours sincerely,

Patrick Weaver

Melbourne, Australia

Note: Research and copies of original documents that support the assertions in this letter can be freely accessed at: https://mosaicprojects.com.au/PMKI-ZSY.php.